|

| Math Muncher |

If you grew up in the 90's and early 2000's, then you remember playing some serious educational games either in school or at home. The funny thing about them was that they never really felt like they were teaching you stuff. You were just having a lot of fun.

But you did learn. You had to! It was the only way to play the game. How can you munch math in Math Muncher without knowing the math?

These games were great ways of teaching children how to learn while having fun with the topics. But there's not that much of this anymore. What happened? Where are the games that, dare I say, made learning fun?

|

| The Oregon Trail |

Birth of the personal computer

Back when personal computers started getting popularized with such gems as the HP 2100 Minicomputer and the Apple II Microcomputer, the general population started getting their hands all over the clickity clacks of computer keyboards. A lot of computers in the 70's beforehand were used primarily for business databases, advanced computations, code encryption/decryption and missile trajectories. This isn't the type of thing that the general population is going to be using a computer for.

While computers have been pretty good for keeping track of budgets and typed notes, people needed software that would make an often expensive computer really worth the novelty.

Enter: video games.

|

| Spacewar, 1961: Often cited as the earliest video game |

Video games were a massive source of growth for computer popularity with the private sector. While they were clunky to get working most of the time (thanks, floppy disks and command prompts), determined users would have tons of fun on simple programs that created understandable objectives to challenge players.

With the combined popularity of computer games, early graphical interfaces (thanks to Xerox, Apple, and Windows) really cemented the popularity of personal computers and elevated them from simple novelties to a household standard.

Use your power for good

|

| Lemonade Stand on Commodore 64 |

When people outside of video game culture think of video games they often think of one of two things: they either think of "child-like" games like Mario, Minecraft, Tetris, and Sonic the Hedgehog or they'll think of violent "murder simulator" games like Mortal Kombat, Call of Duty, Doom, and Grand Theft Auto. Of course, all of these games are very valuable elements in the video game industry; however, assuming that the buck stops there is incredibly short sighted.

Video games have one of their greatest strengths in their ability to teach a player through simple concepts like conveyance and objective based challenges. Games are automated and respond to an individual's input. Computer programs can keep track of performance and adjust based on what an individual player needs to improve on.

While this is a great way to teach digital sports like Pong, Death Match, Capture the Flag, and Gun Game, it is also a tool that can easily be applied to general education subjects.

|

| Snooper Troops |

There are many inherent strengths of using video games as a medium for teaching children (and even adults) educational concepts.

Games are engaging

Video games are, by their very nature, engaging. If the player is not paying attention, they may lose the game and have to start over. Unlike lectures or book reading, video games do not teach passively. Video games teach actively.

|

| Odell Lake |

A player is not only constantly engaged, but staying engaged is actively rewarded. By giving the player a reward (any reward) the player isn't only being rewarded with education.

Let me give you a hypothetical: Somebody tells you to complete a test. A massive test with tons of questions that you don't know. You study for days and have to retake the test multiple times. Once you complete the test, the person who gave you said test tells you, "Your reward is having completed the test."

Is that satisfying? Is it fun to have to deal with a challenge and the only reward you get is no longer having to do the challenge? No, because that makes repeating the challenge the punishment- even worse, it makes any moment spent during the challenge the punishment. You're being conditioned to think, retroactively, that the whole challenge was a negative experience and that you shouldn't do it again. You need a reward of some kind or none of the challenge feels like you've built up to anything.

|

| Cookie Clicker |

Cookie Clicker is a web based game by Orteil. Your goal is to click a cookie, which makes an arbitrary number rise. Once that number is high enough, you can spend it on buying structures which make the number rise without your input. You keep investing your number into buildings that make the same number rise. What is all of this building to? Well, aside from some interesting events once certain upgrades are unlocked... nothing. Your goal is to keep making the number bigger so you can spend it on things that make the number get bigger faster. In a way, it is perpetually rewarding.

People want rewards to show for their work, and if they're willing to sit in front of a screen and click a cookie endlessly for a reward as shallow as a rising number, they're willing to learn math for a similarly shallow reward.

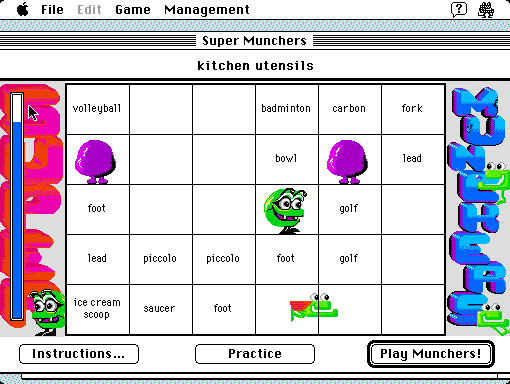

A reward does not need to be shallow, and it is better if the reward isn't shallow. Some good rewards enhance gameplay, such as in Super Munchers, where correctly answering so many questions consecutively results in the Muncher (the player) to become Super Muncher, allowing him to destroy the Troggles who create obstacles in the level.

|

| Super Munchers |

Games don't feel arbitrary

Continuing from the idea of gaining rewards and being engaged, video games don't feel arbitrary. Do you know what does feel arbitrary? A page of exercises soullessly numbered and awaiting completion.

|

| How to hate learning 101 |

In schools, this kind of lack of reason to care about the results of learning exercises is offset by "written problems" where a context is affixed to the exercise. The problem is, however, that this is still incredibly boring and nobody cares.

Keesha has eighteen apples and gives some of them

to Sung. Sung already had four apples. Now Sung

has fourteen apples with those given to him by

Keesha. How many apples does Keesha have?

The answer is that nobody cares about apples. What kind of lifeless bureaucrat was grown in a test tube to write such a boring and politically correct exercise? What child is going to sit in a class and say, "My God! I don't know who Keesha and Sung are, but I need to help them figure out their apple budget!"

Nobody is going to say that. The best you can hope for is a kid who is willing to sift through the crappy paragraph to find the actual math problem and answer it because, you know, they have to.

|

| "I really hope that Keesha gets this apple mess sorted out." |

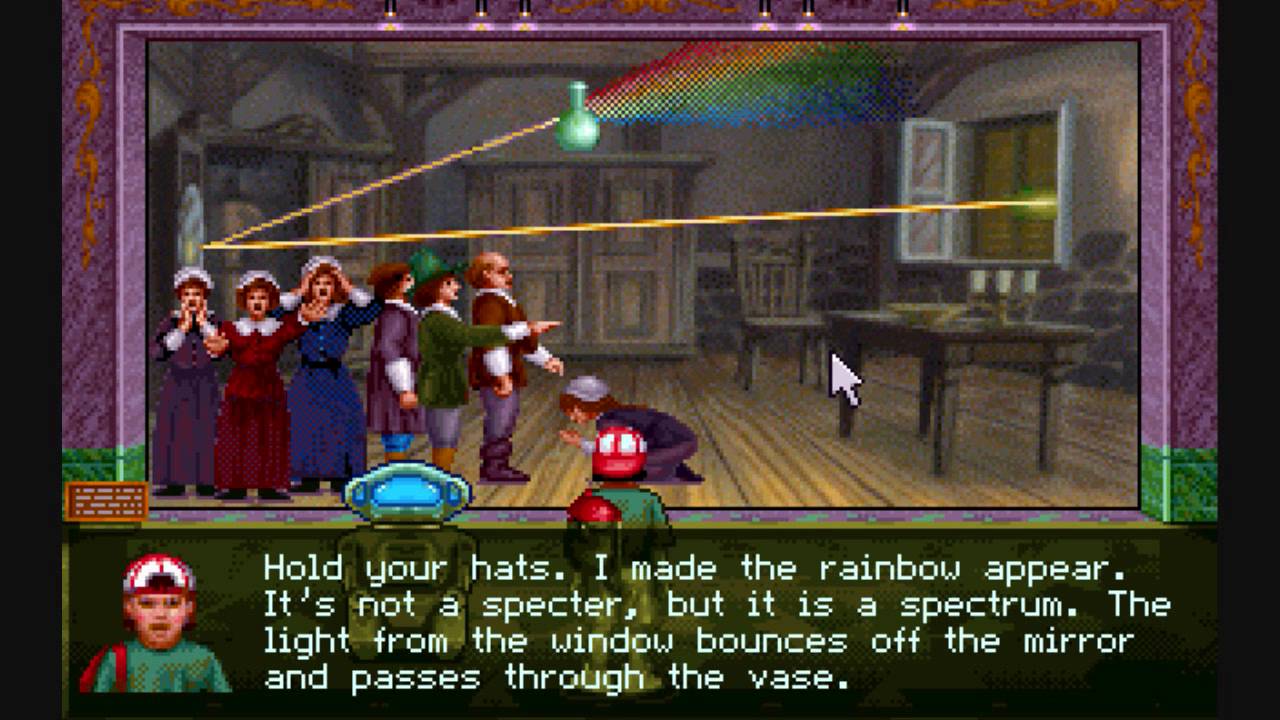

Educational video games don't have this problem (unless they're really, really poorly designed). Who cares about Keesha and her apples when you can be solving math issues in space?!

|

| Math Blaster |

Frankly, even if this were written out in boring text then even the Math Blaster scenario would be boring. By directly engaging the child with a space flight scenario with visuals, sound, rewards, risks, and tension you now have children who really want to learn that math so they can make it through that asteroid field!

Videogames are individualistic

Do you want to know what my least favorite part of school was as a kid? Standardization. We didn't start getting into multiplication until third grade and I knew it in first grade. Do you know what the next step up was after third grade? Nothing until middle school.

It is really important to practice what you learn to maintain retention. But practicing old knowledge should not dominate half of your school life when you could be moving on to advanced methods which contain the old knowledge that you are practicing within them, meaning that you're practicing and learning at the same time.

It's obvious why they do this. Standardization. It's needed in order to allow slower learners to keep up. It makes sense. We shouldn't leave any children behind just because other kids are learning faster.

The problem, however, is that we're not advancing children based on their individual learning. Children who learn faster are being prevented from moving on to the next level. They're stagnating, being bored, being discouraged from further learning because we don't want to separate them from slower learners. It's creating children who have great minds who hate learning environments that hold them back.

Now, we don't have to paint standardization as a villain in every case. However, we can make common core school structures work when we employ computers teaching children proportionate to their own learning levels because computers can easily individualize their lessons.

This is, in my mind, the greatest advantage of educational video games. A child has his or her own profile in the computer program that tracks their proficiency and needed practice within the system to give them lessons catered to them. It allows them to advance at a pace that makes sense for them and take more time on lessons which require practice.

If you want to see how well individualized learning plans can work, head over to Khan Academy and see just how effective it is.

Franchise

|

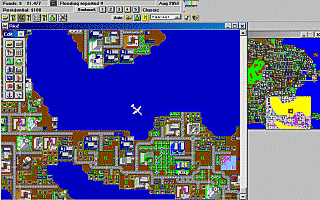

| SimCity |

Imagine if you make a franchise out of learning programs. It's been done. Look at Oregon Trail and SimCity, for example.

Better and more fun learning programs are likely to make more money through scholastic contracts and in-home purchases. What do they do then? They upgrade. They make their learning programs better. They make their scenarios more engaging. They spread to more subjects. Competition creates higher quality learning programs.

There is a lot of potential in educational growth when the effectiveness and popularity of the program directly affect how much funding the developers will get.

So, did educational games do well?

Yes. They did really well! At least, a few of them did.

|

| Museum Madness |

In the 90's, a lot of educational games flourished as popularity of personal computers were booming. Games like Museum Madness, Math Blaster, Word Munchers, SimCity, Oregon Trail, Odell Lake, and Reader Rabbit thrived in both schools and home environments.

|

| Reader Rabbit |

Reader Rabbit announced in 2011 (10 years after its previous release in 2001) a title for the Nintendo Wii. The company which owns it, The Learning Company, also owns The ClueFinders, which is an educational franchise whose last installment was in 2002.

The Oregon Trail franchise received some of the highest praise. Developed and owned by Mecc, The Oregon Trail franchise has persisted from the first release in 1971 well into the current era with releases on smartphone devices like Android and Apple iOS.

|

| The Oregon Trail |

The Munchers series, also developed by Mecc, saw massive popularity and awards in the 80's and 90's but has faded into obscurity moving into the new millennium.

|

| Knowledge Munchers |

SimCity launched Maxis into huge popularity, leading the development studio to make a prolific franchise of Sim games, including more SimCity installments, vehicle simulators like SimCopter, dollhouse genre games like The Sims, and an evolution simulator called Spore. They were acquired by Electronic Arts in 1997 and were closed in 2015 (speculated to be mismanagement under EA).

|

| SimCopter |

Math Blaster, owned by Knowledge Adventure (originally owned by Davidson) is still enjoying a franchise with releases as recently as 2013. Releases are numerous and frequent, keeping the franchise alive.

The Future of Educational Games

Educational software is always popping up and doing well, but there are far fewer educational games on the market today as there were in the 80's and 90's. Not only that, but many of the ongoing franchises are older franchises sticking around with minimal improvements.

The market is wide open for a new game changer. Who is going to make it? A niche is open for the next generation of digital edutainment.

Maybe the next educational software giant will be you.

|

| "Whuh?" |

Want to help me keep making free games? Try checking out my art shop and buying some cool merchandise with my characters and designs on it. It helps me stay alive long enough to make stuff!

No comments:

Post a Comment